by Katrina Brown | May 13, 2020 | Conveyancing, Property Law

Understanding cooling off is critical!

A recent matter has prompted us to write an article warning of the dangers of entering into a contract for the purchase of a property without being absolutely sure that you are ready to do so.

We recently received a call from a client who told us that they had signed an unconditional contract for the purchase of a property the previous day, but after a night of contemplation, the client had decided that the contract made them nervous, as they were waiting on their current property to sell. The client called to ask for our advice on whether they could terminate the contract.

We have found that although many clients are aware that the standard contract for residential purchases in Queensland (the Real Estate Institute of Queensland Contract) contains a statutory clause enabling them to terminate under a five-day cooling off period, they are not aware of the fact that a 0.25% termination penalty applies. On the face of it, 0.25% does not sound like much, but in this instance, when the purchase price was $900,000.00, the termination penalty was $2,250.00.

The client chose to terminate that same day and the seller issued the penalty as anticipated. The issue of the penalty was not changed by the fact that the property sold the following day to another purchaser. The fact that this scenario seems unfair does not change the rights of the seller to impose this penalty.

The worst part of this situation was that it would have been easy for the client to have inserted one special condition into their contract making the contract conditional upon the sale of their current property if they had first sought legal advice (in this instance, there would have been no penalty in the event of termination and the client could have purchased their ideal home without the stress encountered in our client’s situation).

If you need assistance in drafting special conditions into your Contract, please feel free to contact our office on 07 5574 3560.

https://www.qld.gov.au/law/housing-and-neighbours/buying-and-selling-a-property/buying-a-home/making-an-offer-on-a-home/contract-of-sale

by Katrina Brown | Feb 23, 2020 | Commercial Agreements, Commercial Law, Conveyancing, Leasing, Property Law

It comes as a surprise to clients when, on occasion, they find themselves either subject to, or trying to enforce, “informal agreements”. Informal agreements may come in the form of an exchange of discussions in respect to an arrangement, or a signed Lease Offer. It may be that the informal agreement is a sword for a client (for example, the client wants to push the arrangement in the absence of a written contract signed by the parties), or a shield for a client (for example, the client wants to avoid the arrangement because there was no written contract signed by the parties – or the terms were not finally agreed).

Whether the arrangement relates to a supply of goods, services or a commercial leasing arrangement – a legally binding arrangement may be determined by way the conduct of the parties (such as one of the parties completing a condition agreed to start the arrangement (for example, supplying a service), or an exchange of emails about an arrangement), even in the absence of a formal contract – whether or not the contract is ultimately signed.

When are negotiations binding?

Courts look at the objective intention of the parties when determining whether there is a legally binding agreement. That is, whether a reasonable person would consider the agreement to be legally binding, and not the parties’ subjective intention.

Courts have found a legally binding agreement in the following situations:-

- When a vendor and purchaser of commercial property agreed to the essential terms of the agreement over email, noting that the agreement was “subject to contract” and “subject to execution”. A court found that this was essentially an “agreement to contract” and made judgement against the vendor (who attempted to withdraw from the transaction due having found a more favourable third party purchaser);

- Negotiations between a tenant and landlord whereby the essential terms of the lease were agreed upon were found to constitute an agreement to lease. This was the case even though the negotiations began with “subject to formal lease documents being signed” and that not all (minor) terms were agreed. The landlord was ordered to pay damages to the tenant for failing to countersign the formal lease document; and

- A tenant who, after negotiating and signing a letter of offer with a landlord, proceeded to obtain council approvals (with the landlord’s assistance) and took steps to fit-out premises without a formal lease in place was found to be bound by an agreement to lease.

When determining the intention of the parties, regard will be to the surrounding circumstances of the negotiations, the relationship of the parties, subject matter of the agreement and other relevant factors.

What can you do to ensure no binding agreement is in place until documents are signed?

Parties who do not wish to be bound by negotiations or pre-contract documents (e.g. heads of agreement) must ensure that they clearly and consistently reiterate to the other party in all correspondence that no legally binding agreement will be formed until formal and final documentation has been signed. As the above cases reveal, merely stating “subject to contract” is not enough.

Further, prospective tenants should not enter into possession and pay rent until the lease is signed as this may constitute acceptance by conduct. Conversely, a landlord should not accept rent until they are in a position to be bound. More generally, parties should not begin performing their obligations under the agreement before the documents are signed.

However, the risks of making an agreement conditional is as a sword which can be used against you – as the other party to a transaction may similarly withdraw from the arrangement if there is no legally binding agreement. This may mean that you could lose a commercially advantageous deal if it is not locked in.

In any negotiation, you should always seek legal advice before accepting the terms of an agreement (whether by email, orally or otherwise) and before signing any preliminary document.

Nautilus Law Group has a team of professionals experienced in commercial and property agreements. It may be that our team can give you a “thumbs up” or recommendation for variations in a short meeting, or for more complex matters – the engagement may be extended.

Engaging a lawyer to advise on an agreement is an investment in certainty, as the costs of remedying a failed arrangement greatly outweigh the costs savings of avoiding advice.

We welcome you to contact our Property and Commercial Team to discuss your arrangements. Please free to contact Vicki by clicking her name, or by phoning to arrange an appointment with Vicki on (07) 5574 3560.

by Katrina Brown | Jun 11, 2019 | Commercial Law, Conveyancing, Credit Management, Credit Management Advice, Property Law, SMSF, Tax Advisory

The release of PCG 2016/5 comes as no surprise, which follows on the back of the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) publications ATO ID 2015/27 and ATO ID 2015/28, which set the tone for related party Limited Recourse Borrowing Arrangements (LRBAs). The ATO’s 2015 position clarified that nil interest rates and/or interest rate terms being other than “commercial” in nature, constituted “non-arms’ length income” within the meaning of subsection 295.550(1) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA97).

PCG 2016/5 sails past interest rates, and now gives the ATO’s position on the entirety of related party LRBAs, including requirements for principal and interest monthly payments, security, terms of lending and standards for setting fixed and variable interest rates.

IS ANYONE REALLY SURPRISED BY PCG 2016/5?

Given the overriding “sole purpose test” at section 62 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (SISA) – what would lead anyone to think a related party LRBA could be made on other than an “arms’ length” basis, with a commercial standard of reference required? Let’s think this through – we are limited in acquiring assets from members and “related parties” of members by section 66 of the SISA, we are prohibited from providing financial assistance to members and relatives of members by section 65 of the SISA and we are required to deal with investments at an “arms’ length” in accordance with section 109 of the SISA. So, does it come as any real surprise that, if a member or a related party of the member is going to lend money to the self-managed superannuation fund (SMSF), it has to be on commercial terms?

It scares me when Trustees lose sight of the overriding black cloud of Part IVA of the ITAA97, and forget that the ATO has the benefit of hindsight in assessing anti-avoidance schemes. Looking beyond Trustees, those of us advising Trustees must also be alert to our civil, and possible criminal, exposure under SISA, including but not limited to section 55 of the SISA, which puts us, as advisors, on the line to pay losses or damages suffered by any “person” (not limited to members) as a consequence of another “person” (not limited to trustees) involved in a contravention of a SISA covenant. Remembering the Courts and Financial Ombudsman Service quite often favour the consumer, we need only look to section 52 of the SISA to appreciate the broad liability stacked on our shoulders when giving advice to SMSF Trustees of any nature which is other than, on its face, based on all parties acting on commercial arms’ length terms.

Let’s look, therefore, at PCG 2016/5. Whilst the ATO provides us with peace of mind as to its interpretation of “arms’ length terms” for purposes of related party LRBAs in the Safe Harbour provisions, the ATO recognises at paragraph 4 of PCG 2016/5 that other arrangements may nonetheless be based on arms’ length terms.

Safe Harbour 1: The LRBA and real property (commercial or residential)

| Interest Rate |

Reserve Bank of Australia Indicator Lending Rates for banks providing standard variable housing loans for investors. Applicable rates:

– For the 2015-16 year, the rate is 5.75%[1]

– For the 2016 17 and later years, the rate published for May (the rate for the month of May immediately prior to the start of the relevant financial year) |

| Fixed / variable |

Interest rate may be variable or fixed

– Variable – uses the applicable rate (as set out above) for each year of the LBRA

– Fixed – trustees may choose to fix the rate at the commencement of the arrangement for a specified period, up to a maximum of 5 years.

The fixed rate is the rate published for May (the rate for the May before the relevant financial year).

The 2015-16 rate of 5.75% may be used for LRBAs in existence on publication of these guidelines, if the total period for which the interest rate is fixed does not exceed 5 years (see ‘Term of the loan’ below) |

| Term of the loan |

Variable interest rate loan (original) – 15 year maximum loan term (for both residential and commercial)

Variable interest rate loan (re-financing) – maximum loan term is 15 years less the duration(s) of any previous loan(s) relating to the asset (for both residential and commercial)

Fixed interest rate loan – a new LRBA commencing after publication of these guidelines may involve a loan with a fixed interest rate set at the beginning of the arrangement. The rate may be fixed for a maximum period of 5 years and must convert to a variable interest rate loan at the end of the nominated period. The total loan term cannot exceed 15 years.

For an LRBA in existence on publication of these guidelines, the trustees may adopt the rate of 5.75% as their fixed rate, provided that the total fixed-rate period does not exceed 5 years. The interest rate must convert to a variable interest rate loan at the end of the nominated period. The total loan cannot exceed 15 years. |

| Loan to Market Value Ratio (LVR) |

Maximum 70% LVR for both commercial and residential property

If more than one loan is taken out to acquire (or refinance) the asset, the total amount of all those loans must not exceed 70% LVR.

The market value of the asset is to be established when the loan (original or re-financing) is entered into.

For an LRBA in existence on publication of these guidelines, the trustees may use the market value of the asset at 1 July 2015. |

| Security |

A registered mortgage over the property is required |

| Personal guarantee |

Not required |

| Nature and frequency of repayments |

Each repayment is of both principal and interest

Repayments are monthly |

| Loan agreement |

A written and executed loan agreement is required |

Safe Harbour 2: The LRBA and a collection of stock exchange listed shares or units

| Interest Rate |

Reserve Bank of Australia Indicator Lending Rates for banks providing standard variable housing loans for investors plus 2%. Applicable rates:

– For the 2015-16 year, the interest rate is 5.75% + 2% = 7.75%[2]

– For the 2016-17 and later years, the rate published for May plus 2% (the rate for the May before the relevant financial year) |

| Fixed / variable |

Interest rate may be variable or fixed – Variable – uses the applicable rate (as set out above) for each year of the LBRA

– Fixed – trustees may choose to fix the rate at the commencement of the arrangement for a specified period, up to a maximum of 3 years (see ‘Term of the loan’ below). The fixed rate is the rate for May plus 2% (the rate for the May before the relevant financial year)

The 2015-16 rate of 7.75% may be used for LRBAs in existence on publication of these guidelines, if the total period for which the interest rate is fixed does not exceed 3 years (see ‘Term of the loan’ below) |

| Term of the loan |

Variable interest rate loan (original) – 7 year maximum loan term

Variable interest rate loan (re-financing) – maximum loan term is 7 years less the duration(s) of any previous loan(s) relating to the collection of assets

Fixed interest rate loan – a new LRBA commencing after publication of these guidelines may involve a loan that has a fixed interest rate set at the beginning of the arrangement. The rate may be fixed up to for a maximum of 3 years, and must convert to a variable interest rate loan at the end of the nominated period. The total loan term cannot exceed 7 years.

For an LRBA in existence on publication of these guidelines, the trustees may adopt the rate of 7.75% as their fixed rate, provided that the total period of the fixed rate does not exceed 3 years. The interest rate must convert to a variable interest rate loan at the end of the nominated period. The total loan cannot exceed 7 years. |

| LVR |

Maximum 50% LVR

If more than one loan is taken out to acquire (or refinance) the collection of assets, the total amount of all those loans must not exceed 50% LVR.

The market value of the collection of assets is to be established when the loan (original or re-financing) is entered into.

For an LRBA in existence on publication of these guidelines, the trustees may use the market value of the asset at 1 July 2015. |

| Security |

A registered charge/mortgage or similar security (that provides security for loans for such assets) |

| Personal guarantee |

Not required |

| Nature and frequency of repayments |

Each repayment is of both principal and interest

Repayments are monthly |

| Loan agreement |

A written and executed loan agreement is required |

So, what happens if you can’t fit your arrangements into the Safe Harbours? You aren’t sunk just yet.

LET’S CONSIDER THE LOAN TERMS…

If your client borrowed from a commercial lender to on-lend to the SMSF, what does the commercial lender’s terms to the client look like?

To keep this simple, let’s create a reference:

Client Pty Ltd, as Trustee for Client Superfund, borrows from John Smith, the sole director of Client Pty Ltd and sole member of Client Superfund, to acquire Greenacre for $500,000. John borrowed $530,000 from Awesome Bank, secured against his home, on a 30 year interest free term, with the first 5 years being interest free only, with principal and interest from year 6. John gave a personal guarantee, and also offered up security against his personal share portfolio. The LVR was 80% of the combined value of John’s home and his share portfolio. The interest on the loan is variable, based on Awesome Bank’s published rates. Awesome Bank has their own internal assessment processes for determining variable rates. John’s advisor told him that he could on-lend at the Awesome Bank’s rate for the full acquisition value, on matching loan terms. John’s advisor also made sure John registered a mortgage over the property. What happens now?

Can John rely on Awesome Bank’s terms to escape the Safe Harbours? Not entirely.

Awesome Bank has recourse against John’s income as well, as the security and later acquired assets of John (through the personal guarantee). John only has recourse against the real property owned by the SMSF, and nothing else. Accordingly, given the additional risk, one would expect a commercial lender in John’s position would have either required higher interest rates, shorter terms or a varied LVR. However, the terms of Awesome Bank’s lending to John are nonetheless material; the first approach for John is to seek out Awesome Bank’s LRBA terms. If Awesome Bank’s LRBA terms at the time of acquisition were more lenient than the Safe Harbour provisions, John has a commercial “arms’ length” reference to hold to support a variation from the Safe Harbour. However, to the extent his LRBA terms are more favourable than the Awesome Bank’s LRBA terms, John would need to vary his own LRBA to match (even if the variation was less than the Safe Harbour provisions).

What if Awesome Bank did not offer LRBA lending at the time of acquisition? Perhaps John could then look to Community Bank instead. If Community Bank has lending terms which were more lenient than the Safe Harbour provisions, then John would have a commercial “arms’ length” reference to support a variation.

To the extent John tries to find “arms’ length” terms different to the Safe Harbour provisions, he is best to ensure the comparative is truly “commercial”. John should not look to his best mate Bob, who is a third party lender, to provide the “commercial” comparative – unless Bob is a recognised credit provider who has engaged in LRBA arrangements as a regular component of his business (which business commenced well before the publication of ATO ID 2015/27 and ATO ID 2015/28).

LET’S CONSIDER SOME STRATEGIES…

Let’s say that John has to figure out how to raise the shortfall in the LVR. What are some options?

- John could make additional concessional and non-concessional contributions (subject to the contribution caps and restrictions) by allowing part of the loan to be paid down (do not forget the paperwork and required transactions!);

- John could invite new members to the fund and their rollovers and/or contributions could be used to reduce the loan (make sure the investment strategy is considered for each);

- John could sell the asset (which could be difficult by 30 June – but it is an option); and/or

- John could re-finance through Awesome Bank, and give Awesome Bank a personal guarantee (hopefully Awesome Bank values his business).

What if John is in pension phase, and he has to fund increased repayments on the LRBA from the SMSF? John could look to any of the above options, and he could also:

- Commute his pension and roll back to growth phase;

- Commute his pension, and commence a part pension with the balance of his member interest in growth phase; and/or

- Vary the terms of his pension to reduce his payments to the statutory minimums.

PCG 2016/5 is not the end of the world, but it is a wake-up call to all advisors in the SMSF space to favour conservatism in strategies. There may be litigation which flows out of PCG 2016/5, given some advisors made exceedingly ambitious strategic recommendations to clients who will not be able to float adequate remedial action by 30 June 2016. The ATO has given advisors a bit of leeway and, with a bit of creative manoeuvring, many SMSFs can sail to the Safe Harbours with minimal frustration (consider the above options, if the client could fund to lend – the client may likely remediate by treating funds as contributions).

If you would like to discuss PCG 2016/5 or what the ATO Safe Harbours mean for you or your clients, please contact Katrina Brown on 07 5574 3560 or via email.

Next Article: Can an Employee acquire a residential property as an investment in the Employee’s Self Managed Super Fund (“SMSF”), if the Employer is a Property Developer?

Previous Article: A complying self-managed superannuation fund may be settled by an instrument having the effect of a deed – allowing for execution by digital signature

by Katrina Brown | May 26, 2016 | Conveyancing, Powers of Attorney and Estate Planning, Property Law, Succession Law

If you hold real property with another person, it is important to know whether you hold the property as joint tenants or as tenants in common.

What’s the difference?

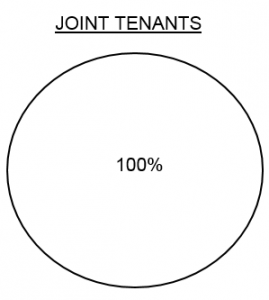

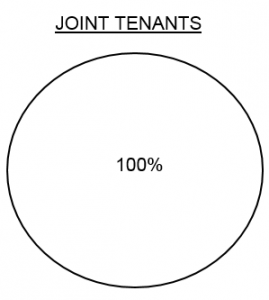

A joint tenancy is where two (or more) people (or legal entities) own an asset jointly – that is 100% of the asset is held in ALL names. No one owner has a fixed interest in the asset. This is commonly the situation between spouses. When one owner of the asset dies, their death is recorded and the asset automatically transfers into the name of the surviving owner. A “jointly held” asset does not (except in some instances in New South Wales) pass to your estate – it passes to the survivor automatically.

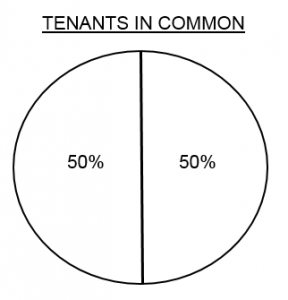

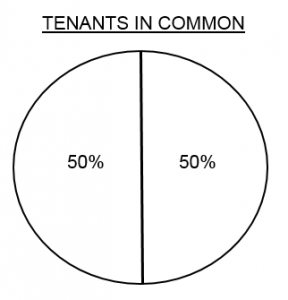

Conversely, a tenancy in common is where two (or more) people (or legal entities) own an asset, but each person owns a specified share. This situation is common in business dealings and in dealings where parties wish to own distinct interests in an asset. The below diagram shows a “tenancy in common” between a husband and wife, with the husband owning 50% of the asset, and the wife owning 50% of the asset. On the death of one of the spouses, their share passes to their estate and is distributed in accordance with their Will. The share does not pass automatically to the surviving spouse.

There are benefits and downsides to each type of holding; accordingly, owners need to be aware of the consequences of each option – to ensure suitability.

What happens if I want to change the way the asset is held?

If you hold an asset as joint tenants, and wish to sever the tenancy, or if you hold the property as tenants in common in equal shares and want to become joint tenants, it is possible to change the way the property is held. These transactions are commonly effected for estate planning or family law purposes.

This change is effected by way of a form signed by one or both property owners, which is then stamped and registered with the Titles Registry as a change of tenure transaction. In some circumstances, there is a transfer duty exemption which can apply.

If you wish to discuss changing the tenure on your property, please contact our office on 07 5574 3560.

by Katrina Brown | Apr 8, 2016 | Commercial Law, Conveyancing, Credit Management, Credit Management Advice, Property Law, Tax Advisory

The release of PCG 2016/5 comes as no surprise, which follows on the back of the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) publications ATO ID 2015/27 and ATO ID 2015/28, which set the tone for related party Limited Recourse Borrowing Arrangements (LRBAs). The ATO’s 2015 position clarified that nil interest rates and/or interest rate terms being other than “commercial” in nature, constituted “non-arms’ length income” within the meaning of subsection 295.550(1) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA97).

PCG 2016/5 sails past interest rates, and now gives the ATO’s position on the entirety of related party LRBAs, including requirements for principal and interest monthly payments, security, terms of lending and standards for setting fixed and variable interest rates.

IS ANYONE REALLY SURPRISED BY PCG 2016/5?

Given the overriding “sole purpose test” at section 62 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (SISA) – what would lead anyone to think a related party LRBA could be made on other than an “arms’ length” basis, with a commercial standard of reference required? Let’s think this through – we are limited in acquiring assets from members and “related parties” of members by section 66 of the SISA, we are prohibited from providing financial assistance to members and relatives of members by section 65 of the SISA and we are required to deal with investments at an “arms’ length” in accordance with section 109 of the SISA. So, does it come as any real surprise that, if a member or a related party of the member is going to lend money to the self-managed superannuation fund (SMSF), it has to be on commercial terms?

It scares me when Trustees lose sight of the overriding black cloud of Part IVA of the ITAA97, and forget that the ATO has the benefit of hindsight in assessing anti-avoidance schemes. Looking beyond Trustees, those of us advising Trustees must also be alert to our civil, and possible criminal, exposure under SISA, including but not limited to section 55 of the SISA, which puts us, as advisors, on the line to pay losses or damages suffered by any “person” (not limited to members) as a consequence of another “person” (not limited to trustees) involved in a contravention of a SISA covenant. Remembering the Courts and Financial Ombudsman Service quite often favour the consumer, we need only look to section 52 of the SISA to appreciate the broad liability stacked on our shoulders when giving advice to SMSF Trustees of any nature which is other than, on its face, based on all parties acting on commercial arms’ length terms.

Let’s look, therefore, at PCG 2016/5. Whilst the ATO provides us with peace of mind as to its interpretation of “arms’ length terms” for purposes of related party LRBAs in the Safe Harbour provisions, the ATO recognises at paragraph 4 of PCG 2016/5 that other arrangements may nonetheless be based on arms’ length terms.

Safe Harbour 1: The LRBA and real property (commercial or residential)

| Interest Rate |

Reserve Bank of Australia Indicator Lending Rates for banks providing standard variable housing loans for investors. Applicable rates:

– For the 2015-16 year, the rate is 5.75%[1]

– For the 2016 17 and later years, the rate published for May (the rate for the month of May immediately prior to the start of the relevant financial year) |

| Fixed / variable |

Interest rate may be variable or fixed

– Variable – uses the applicable rate (as set out above) for each year of the LBRA

– Fixed – trustees may choose to fix the rate at the commencement of the arrangement for a specified period, up to a maximum of 5 years.

The fixed rate is the rate published for May (the rate for the May before the relevant financial year).

The 2015-16 rate of 5.75% may be used for LRBAs in existence on publication of these guidelines, if the total period for which the interest rate is fixed does not exceed 5 years (see ‘Term of the loan’ below) |

| Term of the loan |

Variable interest rate loan (original) – 15 year maximum loan term (for both residential and commercial)

Variable interest rate loan (re-financing) – maximum loan term is 15 years less the duration(s) of any previous loan(s) relating to the asset (for both residential and commercial)

Fixed interest rate loan – a new LRBA commencing after publication of these guidelines may involve a loan with a fixed interest rate set at the beginning of the arrangement. The rate may be fixed for a maximum period of 5 years and must convert to a variable interest rate loan at the end of the nominated period. The total loan term cannot exceed 15 years.

For an LRBA in existence on publication of these guidelines, the trustees may adopt the rate of 5.75% as their fixed rate, provided that the total fixed-rate period does not exceed 5 years. The interest rate must convert to a variable interest rate loan at the end of the nominated period. The total loan cannot exceed 15 years. |

| Loan to Market Value Ratio (LVR) |

Maximum 70% LVR for both commercial and residential property

If more than one loan is taken out to acquire (or refinance) the asset, the total amount of all those loans must not exceed 70% LVR.

The market value of the asset is to be established when the loan (original or re-financing) is entered into.

For an LRBA in existence on publication of these guidelines, the trustees may use the market value of the asset at 1 July 2015. |

| Security |

A registered mortgage over the property is required |

| Personal guarantee |

Not required |

| Nature and frequency of repayments |

Each repayment is of both principal and interest

Repayments are monthly |

| Loan agreement |

A written and executed loan agreement is required |

Safe Harbour 2: The LRBA and a collection of stock exchange listed shares or units

| Interest Rate |

Reserve Bank of Australia Indicator Lending Rates for banks providing standard variable housing loans for investors plus 2%. Applicable rates:

– For the 2015-16 year, the interest rate is 5.75% + 2% = 7.75%[2]

– For the 2016-17 and later years, the rate published for May plus 2% (the rate for the May before the relevant financial year) |

| Fixed / variable |

Interest rate may be variable or fixed – Variable – uses the applicable rate (as set out above) for each year of the LBRA

– Fixed – trustees may choose to fix the rate at the commencement of the arrangement for a specified period, up to a maximum of 3 years (see ‘Term of the loan’ below). The fixed rate is the rate for May plus 2% (the rate for the May before the relevant financial year)

The 2015-16 rate of 7.75% may be used for LRBAs in existence on publication of these guidelines, if the total period for which the interest rate is fixed does not exceed 3 years (see ‘Term of the loan’ below) |

| Term of the loan |

Variable interest rate loan (original) – 7 year maximum loan term

Variable interest rate loan (re-financing) – maximum loan term is 7 years less the duration(s) of any previous loan(s) relating to the collection of assets

Fixed interest rate loan – a new LRBA commencing after publication of these guidelines may involve a loan that has a fixed interest rate set at the beginning of the arrangement. The rate may be fixed up to for a maximum of 3 years, and must convert to a variable interest rate loan at the end of the nominated period. The total loan term cannot exceed 7 years.

For an LRBA in existence on publication of these guidelines, the trustees may adopt the rate of 7.75% as their fixed rate, provided that the total period of the fixed rate does not exceed 3 years. The interest rate must convert to a variable interest rate loan at the end of the nominated period. The total loan cannot exceed 7 years. |

| LVR |

Maximum 50% LVR

If more than one loan is taken out to acquire (or refinance) the collection of assets, the total amount of all those loans must not exceed 50% LVR.

The market value of the collection of assets is to be established when the loan (original or re-financing) is entered into.

For an LRBA in existence on publication of these guidelines, the trustees may use the market value of the asset at 1 July 2015. |

| Security |

A registered charge/mortgage or similar security (that provides security for loans for such assets) |

| Personal guarantee |

Not required |

| Nature and frequency of repayments |

Each repayment is of both principal and interest

Repayments are monthly |

| Loan agreement |

A written and executed loan agreement is required |

So, what happens if you can’t fit your arrangements into the Safe Harbours? You aren’t sunk just yet.

LET’S CONSIDER THE LOAN TERMS…

If your client borrowed from a commercial lender to on-lend to the SMSF, what does the commercial lender’s terms to the client look like?

To keep this simple, let’s create a reference:

Client Pty Ltd, as Trustee for Client Superfund, borrows from John Smith, the sole director of Client Pty Ltd and sole member of Client Superfund, to acquire Greenacre for $500,000. John borrowed $530,000 from Awesome Bank, secured against his home, on a 30 year interest free term, with the first 5 years being interest free only, with principal and interest from year 6. John gave a personal guarantee, and also offered up security against his personal share portfolio. The LVR was 80% of the combined value of John’s home and his share portfolio. The interest on the loan is variable, based on Awesome Bank’s published rates. Awesome Bank has their own internal assessment processes for determining variable rates. John’s advisor told him that he could on-lend at the Awesome Bank’s rate for the full acquisition value, on matching loan terms. John’s advisor also made sure John registered a mortgage over the property. What happens now?

Can John rely on Awesome Bank’s terms to escape the Safe Harbours? Not entirely.

Awesome Bank has recourse against John’s income as well, as the security and later acquired assets of John (through the personal guarantee). John only has recourse against the real property owned by the SMSF, and nothing else. Accordingly, given the additional risk, one would expect a commercial lender in John’s position would have either required higher interest rates, shorter terms or a varied LVR. However, the terms of Awesome Bank’s lending to John are nonetheless material; the first approach for John is to seek out Awesome Bank’s LRBA terms. If Awesome Bank’s LRBA terms at the time of acquisition were more lenient than the Safe Harbour provisions, John has a commercial “arms’ length” reference to hold to support a variation from the Safe Harbour. However, to the extent his LRBA terms are more favourable than the Awesome Bank’s LRBA terms, John would need to vary his own LRBA to match (even if the variation was less than the Safe Harbour provisions).

What if Awesome Bank did not offer LRBA lending at the time of acquisition? Perhaps John could then look to Community Bank instead. If Community Bank has lending terms which were more lenient than the Safe Harbour provisions, then John would have a commercial “arms’ length” reference to support a variation.

To the extent John tries to find “arms’ length” terms different to the Safe Harbour provisions, he is best to ensure the comparative is truly “commercial”. John should not look to his best mate Bob, who is a third party lender, to provide the “commercial” comparative – unless Bob is a recognised credit provider who has engaged in LRBA arrangements as a regular component of his business (which business commenced well before the publication of ATO ID 2015/27 and ATO ID 2015/28).

LET’S CONSIDER SOME STRATEGIES…

Let’s say that John has to figure out how to raise the shortfall in the LVR. What are some options?

- John could make additional concessional and non-concessional contributions (subject to the contribution caps and restrictions) by allowing part of the loan to be paid down (do not forget the paperwork and required transactions!);

- John could invite new members to the fund and their rollovers and/or contributions could be used to reduce the loan (make sure the investment strategy is considered for each);

- John could sell the asset (which could be difficult by 30 June – but it is an option); and/or

- John could re-finance through Awesome Bank, and give Awesome Bank a personal guarantee (hopefully Awesome Bank values his business).

What if John is in pension phase, and he has to fund increased repayments on the LRBA from the SMSF? John could look to any of the above options, and he could also:

- Commute his pension and roll back to growth phase;

- Commute his pension, and commence a part pension with the balance of his member interest in growth phase; and/or

- Vary the terms of his pension to reduce his payments to the statutory minimums.

PCG 2016/5 is not the end of the world, but it is a wake-up call to all advisors in the SMSF space to favour conservatism in strategies. There may be litigation which flows out of PCG 2016/5, given some advisors made exceedingly ambitious strategic recommendations to clients who will not be able to float adequate remedial action by 30 June 2016. The ATO has given advisors a bit of leeway and, with a bit of creative manoeuvring, many SMSFs can sail to the Safe Harbours with minimal frustration (consider the above options, if the client could fund to lend – the client may likely remediate by treating funds as contributions).

If you would like to discuss PCG 2016/5 or what the ATO Safe Harbours mean for you or your clients, please contact Katrina Brown on 07 5574 3560 or via email.

by Katrina Brown | Jul 28, 2015 | Body Corporate Law, Constitution and by-law advice, Conveyancing

Due diligence searches are an important factor when purchasing a commercial or residential property, and ensuring you are considering all important information is key to determining that the investment is sound and whether to proceed with the transaction.

As body corporate solicitors, we strongly urge all potential buyers of strata property to consider a thorough search of the historical minutes, financials and general communications available in the strata records to ascertain how the body corporate is functioning and to appreciate what expenses are anticipated. A search of the strata agenda, minutes, resolutions and other records available on a Body Corporate Records Inspection can demonstrate how well the property functions generally (for example, is the property governed by a dysfunctional committee and/or are there owners who make resolving Strata matters difficulty and/or are there expenses unmet (such as a roof repair that has been considered, but not addressed requiring a special levy). In addition to the “standard searches,” we strongly urge clients to conduct a Body Corporate Records Inspection to find the “skeleton in the closet.”

What is a Body Corporate Records Inspection?

A Body Corporate Records Inspection is a physical inspection of all records held by the relevant body corporate. Depending on the size and age of the body corporate, the records are anywhere from the size of a binder folder, to the size of several archive boxes. While the amount of information to be reviewed can be slightly overwhelming, it is important to examine all relevant records.

What do you look at in a Body Corporate Records Inspection?

As a general rule of thumb, we suggest reviewing all body corporate records from the previous 3 years.

There are, however, key documents that we would suggest reviewing:-

Recent accounts statements for the administrative and sinking funds will indicate the current balance of each fund. Bear in mind that the administrative fund pays for ongoing, day-to-day expenses (this can include gardening, general maintenance, insurance, body corporate manger’s fees), whereas the sinking fund pays for capital expenses (such as painting).

It is important to ensure there are sufficient funds coming into and maintained in the administrative account to fund ongoing expenses (there should be numerous transactions on this account), and to check the balance of the sinking fund (which, in most cases, rises steadily – if the account is decreasing, there may be large capital improvements that have been made for you to investigate).

Review and compare the balance sheet and budget for the current and prior financial years – look at whether there are any significant changes to the budget or balance sheet that are unexplained, and to ensure that levies charged throughout the financial year are sufficient to cover the budget for that year.

The body corporate may have commissioned reports for specific inspections of the complex – such as fire inspections, general building and pest inspections, or structural reports. Review these reports in detail to check for any concerns raised or recommendations made by the report writer, and check the body corporate records as to whether these have been addressed.

Make a copy of the body corporate insurance (if you are obtaining finance, you will generally need to provide this to your lender). Review the insurance to ensure it covers all crucial elements, and check whether the building is insured for the recommended amount.

Review the By-Laws for any changes and to ensure you have received the most current copy. Remember that the owner and tenant of the complex must ensure that these By-Laws are complied with at all times.

Although this covers a broad range of information to review, it is crucial that the correspondence is thoroughly reviewed – it might only be one line in an email that is enough to raise a “red flag” of a potential issue.

Unfortunately, there is no cheap or easy way to do the records inspection – however, while combing through several years of information about the body corporate can be time consuming, it is certainly a worthwhile exercise.

Residential Case Study: Jane’s purchase of Unit 3 University Drive

Jane signed a Contract for the purchase of Unit 3 University Drive – a unit on the second floor of a two story building (which is around 15 years old), in which there are eight units. The Contract contained a specific provision that she was permitted 14 days to conduct a body corporate records inspection, and had the right to terminate if the results were not satisfactory. When Jane initially provided her instructions, she advised she didn’t think the records inspection was necessary – the building looked stable, the unit was just intended to be an investment property, and the cost of the inspection was too high (at a few hundred dollars). Despite her solicitor warning of the potential issues that could be uncovered in a body corporate records inspection, Jane confirmed she didn’t want to pay for the inspection and to only conduct standard searches.

Her lawyer telephoned Jane on the date the condition was due to confirm she was prepared to let the date pass with no action, and did not require the search to be conducted – during the telephone call, Jane had a change of heart and requested that the inspection be conducted and results advised immediately (please try to avoid doing this to your solicitor – while we appreciate that you may change your mind, short notice of a change of your instructions may result in insufficient time to conduct the search – it is best to give your solicitor as much notice as possible). The lawyer was able to arrange an inspection of the records, and attended at the body corporate’s office to inspect same that afternoon. The person inspecting the records initially went through 3 years’ worth of records (as we suggest above) but, due to the size of the body corporate and age of the building, decided to inspect records back to 4 years instead.

A one line email 2 days before the 4 year mark was to the effect of one owner of a unit complaining that the structural issues with the building of their earlier email (dating back approximately one year prior) had not been resolved. This caused concern with the inspector, who then reviewed older reports and correspondence, which indicated that there was structural cracking in the building at two places, that could only be fixed by costly repairs (in the sum of approximately $40,000).

This outcome was reported to Jane, who, on the basis that the issue was unresolved (and assumed to have worsened due to inaction over the prior 4 years), elected to terminate the contract.

Commercial Case Study: John’s purchase of Unit 1 Industrial Estate

John signed a Contract for the purchase of a commercial unit from which he was going to run a manufacturing workshop. His contract contained a 14 day due diligence clause and he gave his solicitor immediate instructions to conduct a records inspection.

Upon inspection of the records, correspondence indicated complaints from unit owners of cracking in the foundation of the central carpark of the complex. Further investigation into the reports obtained by the body corporate revealed that the cracking was caused by the foundation of the building “slipping”, and indicated that action would eventually need to be taken, but was not yet critical. The body corporate had resolved that no action was to be taken at present, but was aware that the cost to repair the damage caused and to prevent further “slipping” was in the vicinity of $100,000.

Further investigation into the balance of the sinking fund indicated that the body corporate held approximately $300,000.

On the basis that the body corporate held a sufficient sum in the sinking fund so as to fund the repairs in the future, John did not object to the outcome of the records inspection and satisfied the condition.

What happens if I find a problem when I conduct an inspection?

If your lawyer reviews the contract for the purchase of a unit or apartment before you have sign it, they will most likely recommend that either a “due diligence” or “body corporate records inspection” clause be inserted. These types of clauses allow the buyer to inspect the records and, if an issue is revealed through the course of such investigations, will give rise to rights under the contract (such as to terminate). If you are alerted to an issue with a records inspection, we recommend you contact your lawyer as soon as possible to discuss appropriate action and to obtain advice as to your options. Once you have been fully informed of these matters, you can provided instructions on how you wish to proceed.

If you are considering purchasing a property that is part of a body corporate or have any questions about body corporate records inspections, please contact our Property Team on 07 5574 3560. Thank you, Katrina Brown, Senior Lawyer.